Нелюбовь (Loveless) film analysis

In Mythologies, Barthes emerges as primarily a literary theorist who deconstructs signs and myths to “libterat[e] the signifier.”[1] In his 1960 essay, Le Problème de la signification au cinema, he queries “to what extent does semiology have rights over the analysis of film?”[2] That is, he questions whether the ideological operation of the process of semiotic analysis even applies in film, where he feels that the meta-language and realm of signification reflects the individual spectator’s “yearning intentionality of the imagination,”[3] or rather, subjective desire to give meaning to what they see, feel, notice.[4] Barthes subsequently went on to develop the theory of punctum, whereby when an individual chooses to engage in semiotic analysis in relation to photography, art and film “singularly arresting to him or her.”[5] Subsequently commentators on Barthes works have stressed the “private nature of the experience”[6] of semiotic analysis of art, photography and film thus embedding the personal attribution of “denotative”[7] power within semiotic analysis of these broad categories of objects themselves. Indeed, in choosing an object of analysis for this essay, I chose my favourite Russian film Loveless,[8] so much adored that I visited the abandoned filming location when previously travelling through the country (Figure 1, cross referencing Figure 2). Not only is this choice a reflection of a my connection to Russia, and feeling of anchorage to the subject of Russia, but arguably the following semiotic analysis serves as a means for challenging and “judging”[9] my own personal conceptions in relation to the subject.[10]

Figure 1: Screenshot from Loveless inside an abandoned building

Figure 2: Researchers own photograph of filming location Alabushevo, Moskovskaya Oblast, Russia.

Loveless

Andrey Zvyagintsev’s 2017 Russian language film Loveless explores the dysfunctional relationships between a divorced Muscovite couple (Zhenya, a cosmetologist, and Boris, a banker), their lovers, and their son (Alyosha). Following a fight between the couple regarding their respective hatred of their parental responsibilities to Alyosha, he leaves for school the next morning never to be seen again, leaving both Zhenya and Boris devastated even in their previously happy affairs. Loveless arguably does not only offer only a picture of the personal immaturity and social emptiness of its characters, but rather, represents a social diagnosis of Russian society. Taking an inductive approach, it is argued that the overriding second level sign that the film represents is that the Russian state is in civilizational catastrophe. Within the film itself, there is an plentiful system of signifiers in the form of film components (plot, dialogue, prop, costume, characters) that critique the socio-political reproduction of traditional values and politics, and the absence of working societal institutions in Russia as will be briefly explored in the remainder of this piece.

Traditionalism

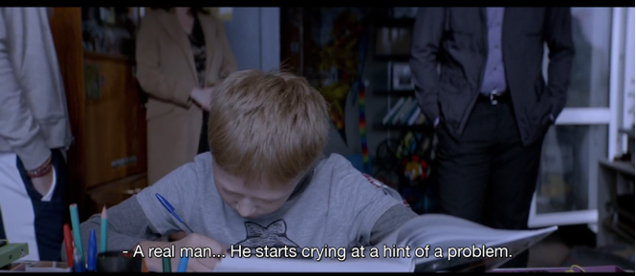

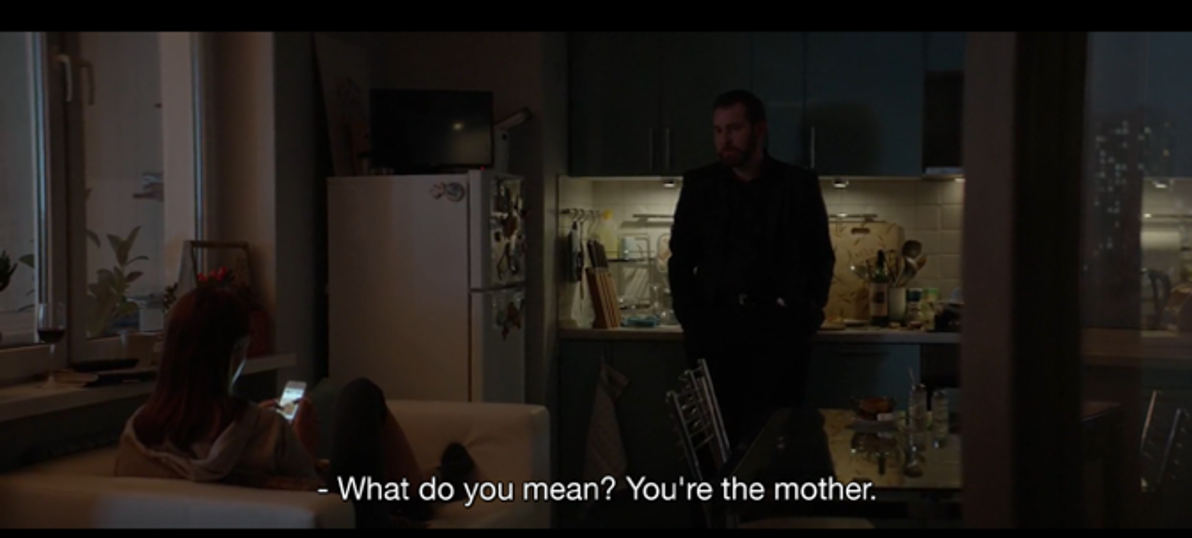

The family, as the first unavoidable social basis of creation of human classifications, becomes bound in the rhythm of semiotic reproduction of traditional roles in Russian society, which an overt focus on gender.[11] Both Boris and Alyosha are often “devirilized”[12] for showing emotion or being weak (Figure 3). Zhenya (portrayed in and of herself as Mother Russia - Figure 4) is also chastised for not adhering to the created boundaries for the conceptual classification of motherhood (Figure 5), is selfish, and is narcissistically associated mostly with mindless modernisation, being attached her iPhone, makeup and TV. The heatedness of conflict surrounding the gender roles expected of each other between Boris and Zhenya (Figure 6) further stands in sharp contrast to the dull mise-en-scène, and other quiet conversations throughout the film. The mortifying silhouette of gender configuration in the film characters through a codex of signifiers, unveils a conception held in modern Russian public consciousness, where to subvert traditionalism in favour of modernity causes destruction, and even death (second level sign).

Figure 3: "A real man... He starts crying at a hint of a problem."

Figure 4: Zhenya wearing a "Russian" Olympic tracksuit

Figure 5: "What do you mean? You're the mother."

Figure 6: "You hit it and quit if, you shit here, shit there, and she'll clean up the mess, right?"

“Morality politics”[13]

Going further in relation to the construction of Russian society, Boris’ workplace, if emptied out of its meaning, is arguably a signified representation of the Russian regime. The bank tacitly forbids employees to divorce, and Zhenya goes so far as to deem the bank as having a system of “Orthodox shariah” (Figure 7). The bank (the first level sign), is really the modern Russian state, the defender of traditional values (second level sign). It can further be observed that punishment for perceived moral transgressions such as divorce can be avoided by lying to the bank about ones marital status (and indeed, one employee goes so far as to hire a fake family “because everybody has to be with a family, with children” - Figure 8). In this way, the “morality politics”[14] of the workplace, or rather the Russian regime, can be understood as not just condemning transgression of the societal rules, but the lack of preservation of the appearance of existential rightness and appropriateness (second level sign). This also perhaps draws attention to tight Russian state control over the production of cultural narratives more broadly (second level sign).

Figure 7: "He started an Orthodox shariah there"

Figure 8: Boris and a coworker conversing about hiding Boris' divorce from management

The semiotic and the real life mythscape

It is notable that the radio listening to and television watched by subjects always discusses the Russo-Ukrainian conflict (first level sign; Figure 9 and Figure 10). The enduring Russian political myth of foreign encirclement, and of the conspiratorial adversary,[15] is therefore intrinsically interwoven with the depicted onslaught of moral relaxation, however, this threat of foreign depravity is arguably not the second level sign produced by Zvyagintsev. Rather, the director seems to mock this real life mythscape of foreign-led immorality negatively impacting Russian society using his syntax of signifiers to craft a message of his own in relation to internal civic catastrophe. The character of Zhenya (first level sign) arguably, if emptied out of her role as a mother, represents the self-affirming, selfish Mother Russia, who overall lacks care for and engagement with her dependents until it is too late to save them. In turn, the supreme qualities of dependents (Alyosha as first level sign), or rather, the Russian people simply cannot be advanced (second level sign). The completely nonchalant police (first level sign), self-admittedly are unable to play a functional role in the search for Alyosha due to not only “bureaucracy” but also resource scarcity due to elements of the brigade being sent to the Ukraine.[16] A police officer actively suggests self-help and engagement of volunteer search-and-rescue squad Liza Alert (first level sign) to search for Alyosha due to the “real situation” (Figure 11). Zvyagintsev puts forth through this set of signifiers that the abandonment of the Russian ward and disintegration of the physical, social and moral Russian being is a result of a weak rule of law, and absent, routinized state apparatuses co-opted by sanctified, imperial missions rather than social imperatives and individual religio-philosophical failings (second level sign). Indeed, as Zvyagintsev himself postulated even before Loveless’ theatrical release, perhaps “Thomas Hobbes was fundamentally mistaken to idealize the state.”[17]

Figure 9: Still from Loveless depicting a television host "talking about the war in Ukraine"

Figure 10: Still from Loveless depicting a television host "talking about victims of the war in Ukraine"

Figure 11: Police officer addresses Zhenya

References

[1] Roland Barthes translated and quoted in Victor Burgin, "Re-reading Camera Lucida," in The End of Art Theory: Criticism and Postmodernity, ed. Victor Burgin, Communications and Culture (London: Macmillan Education UK, 1986), 76.

[2] Roland Barthes translated and quoted in Elena Oxman, "Sensing the Image: Roland Barthes and the Affect of the Visual," SubStance 39, no. 2 (2010): 75, https://doi.org/10.1353/sub.0.0083.

[3] Roland Barthes translated and quoted in Burgin, "Re-reading Camera Lucida," 80.

[4] Roland Barthes translated and quoted in Oxman, "Sensing the Image: Roland Barthes and the Affect of the Visual," 83.

[5] Michael Fried, "Barthes's Punctum," Critical Inquiry 31, no. 3 (2005), https://doi.org/10.1086/430984.

[6] Burgin, "Re-reading Camera Lucida," 78.

[7] Oxman, "Sensing the Image: Roland Barthes and the Affect of the Visual."

[8] Russian: Нелюбовь.

[9] Emphasis added, David MacDougall, The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses, Course Book. ed. (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2006).

[10] Oxman, "Sensing the Image: Roland Barthes and the Affect of the Visual," 76-77.

[11] Natalya Zelyanskaya, Konstantin Belousov, and Dilara Ichkineeva, "Naive geography and geopolitical semiotics: The semiotic analysis of geomental maps of Russians," Semiotica 2017, no. 215 (2017): 245, https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2016-0231; Zhan Toshchenko, "Trauma and Antinomy: The New Features of Public Consciousness and Behavior in Contemporary Russia," Journal of Sociology and Social Anthropology XVIII, 1 (2015): 54-55.

[12] Lawrence D. Kritzman, "Roland Barthes: The Discourse of Desire and the Question of Gender," Modern Language Notes 103, no. 4 (1988): 854, https://doi.org/10.2307/2905020.

[13] Gulnaz Sharafutdinova, "The Pussy Riot affair and Putin's démarche from sovereign democracy to sovereign morality," Nationalities Papers 42, no. 4 (2014): 615-21, https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2014.917075.

[14] Sharafutdinova, "The Pussy Riot affair and Putin's démarche from sovereign democracy to sovereign morality," 615-21.

[15] Bo Petersson, "Putin and the Russian Mythscape: Dilemmas of Charismatic Legitimacy," Demokratizatsiya 25, no. 3 (2017).

[16] "В Джанкое находится 1-й мотострелковый батальон «Восток»из Чечни," Ворота Крыма 2014, https://jankoy.org.ua/dzhankoe-1-motostrelkovyj-batalon-vostok-chechni/comment-page-1/.

[17] Valery Kichin, "Andrey Zvyagintsev: On art-house film, spirituality and the rule of law," Russia Beyond 2014, https://www.rbth.com/arts/2014/10/28/andrey_zvyagintsev_on_art-house_film_spirituality_and_the_rule_of_law_40933.html; Олег Хархордин, "Андрей Звягинцев как зеркало русской эволюции," Ведомости (2015), https://www.vedomosti.ru/newspaper/articles/2015/02/11/russkii-mir-nastoyaschii-leviafan.